During a week when so many Americans have experienced

some combination of joy, rage, and frustration in seeking the perfect holiday

gifts for their children, it seems appropriate to pause and ask: Where did the

practice of giving Christmas gifts to children come from?

There does not appear to be an easy answer. Gifts do not

primarily serve as rewards: Commentators on the political left

and right

have in recent years asked parents to abandon the “naughty and nice” paradigm

that suggests such presents are prizes for good behavior, and indeed historical

evidence suggests that proper conduct has not been a widespread prerequisite for

young Americans to receive Christmas gifts.

Nor do presents seem to have a clear connection to

Christian faith. Some American families have established a “three-gift”

Christmas in an effort to link the practice to the generosity

of the three wise men in the story of Jesus’s birth, but again no broad

historical precedent exists for this link. In fact, religious leaders have long

been more likely to decry the commercialization of Christmas as detracting from

the true spirit of the holiday than to celebrate the delivery of purchased goods

to middle-class or wealthy children. (Donating gifts to poor children is a

different matter, of course, but that practice became common in the United

States only after gift-giving at home became a well-established

ritual.)

Critics of the commercialization of Christmas tend to

attribute the growth of holiday gift-giving to corporate marketing efforts.

While such efforts did contribute to the magnitude of the ritual, the practice

of buying Christmas presents for children predates the spread of corporate

capitalism in the United States: It began during the first half of the 1800's,

particularly in New York City, and was part of a broader transformation of

Christmas from a time of public revelry into a home and child centered

holiday.

This reinvention was driven partly by commercial

interests, but more powerfully by the converging anxieties of social elites and

middle-class parents in rapidly urbanizing communities who sought to exert

control over the bewildering changes occurring in their cities. By establishing

a new type of midwinter celebration that integrated home, family, and shopping,

these Americans strengthened an emerging bond between Protestantism and consumer

capitalism.

In his book The Battle for

Christmas, the historian Stephen Nissenbaum presents the

19th-century reinvention of the holiday as a triumph of New York’s elites over

the city’s emerging working classes.

New York’s population grew nearly tenfold

between 1800 and 1850, and during that time elites became increasingly

frightened of traditional December rituals of “social inversion,” in which

poorer people could demand food and drink from the wealthy and celebrate in the

streets, abandoning established social constraints much like on Halloween night

or New Year’s Eve.

These rituals, which occurred any time between St. Nicholas

Day (a Catholic feast day observed in Europe on December 6th) and New Year’s

Day, had for centuries been a means of relieving European peasants’ (or American

slaves’) discontent during the traditional downtime of the agricultural cycle.

In a newly congested urban environment, though, aristocrats worried that such

celebrations might become vehicles for protest when employers refused to give

workers time off during the holidays or when a long winter of unemployment

loomed for seasonal laborers.

In response to these concerns, a group of wealthy men who

called themselves the Knickerbockers invented a new series of traditions for

this time of year that gradually moved Christmas celebrations out of the city’s

streets and into its homes. They presented these traditions as a reinvigoration

of Dutch customs practiced in New Amsterdam and New York during the colonial

period, although Nissenbaum and other scholars have established that these

supposed antecedents largely did not exist in North America.

Drawing from two

story collections by Washington Irving, their most well-known member, these New

Yorkers experimented with domestic festivities on St. Nicholas Day and New

Year’s Day until another member of the group, Clement Clark Moore, solidified

the tradition of celebrating on Christmas with his enormously popular poem “A

Visit from St. Nicholas” (better known as “The Night Before Christmas”) in

1822.

The St. Nicholas that Moore presented in his famous poem

was not a wholesale invention, but like the other traditions the Knickerbockers

borrowed and transformed, he was not a well-established part of New York’s

winter holiday rituals. Similarly, his delivery of presents to children aligned

with a newly emerging practice in 1820's New York, although the giving of

homemade gifts during the winter holidays appears to have begun by the late

1700's. Moore’s poem does not explain why children are receiving presents on

Christmas, although they clearly have the expectation of receiving special

treats (“visions of sugar plums danced in their heads”).

Understanding why giving gifts to children (and by

gradual extension, to adults) became part of this new Christmas tradition

requires an expansion of Nissenbaum’s story. The Battle for

Christmas focuses on the tensions between New York’s elites

and its working classes, but during this same period, a middle class began to

emerge in New York and other northern cities, and the reinvention of Christmas

served their purposes as well.

Like their wealthier contemporaries, middle-class

families worried about what rapid population growth and expanding market

capitalism would do to their children—particularly because an expansion of goods

and services on offer was reducing young people’s household responsibilities at

a time when alternative pathways to adulthood, such as public education, had yet

to emerge.

In response to the increasing uncertainty surrounding

this stage of life, urban families that aspired to prepare their children for

life in the middle and upper ranks of American society widely adopted new

strategies for child-rearing. As work and home became increasingly separated for

these families, parents kept children within the home (or at church or in

school) as long as possible in order to avoid what many of them perceived as the

corrupting influences of commerce on kids’ inchoate moral character. Elites’

efforts to domesticate Christmas aligned neatly with these parents’ interests,

for they encouraged young Americans to associate the joys of the holiday with

the morally and physically protective space of home.

Meanwhile, even if parents were concerned about

commercial influences outside the home, they were not bothered by the idea of

letting children’s commodities into it, in limited doses. In the 1820's, an

American toy industry began to emerge, and American publishers started producing

books and magazines for children. (The first three self-sustaining children’s

magazines in U.S. history debuted between 1823 and 1827.) Much of the initial

demand for these items reflected parents’ recognition of the instructional power

of consumer goods. As an 1824 review of the evangelical children’s magazine

The Youth’s Friend noted,

Let the Youth’s Magazine be called his own paper, and how will the juvenile reader clasp it to his bosom in ecstacy [sic] as he takes it from the Post-Office. And if instruction from any source will deeply affect his heart, it will when communicated through the medium of this little pamphlet.

If early 19th-century newspaper ads promoting bibles as

children’s Christmas gifts are any indication, parents during this era seem to

have retained a similar focus on delivering spiritual value to their children.

After the Civil War, the spread of consumer products in American cities made it

increasingly difficult to control children’s access to toys, books, and

magazines, so in order to keep young people at home, parents gradually

acquiesced to purchasing products intended to amuse as well as instruct their

offspring.

Postbellum Christmas traditions followed this broader

trend by becoming more child-focused, particularly through the reconstructed

image of St. Nicholas. Clement Clark Moore’s St. Nick was an elf who was jolly

but also a bit scary (as indicated by the narrator’s repeated reminder that he

had “nothing to dread”).

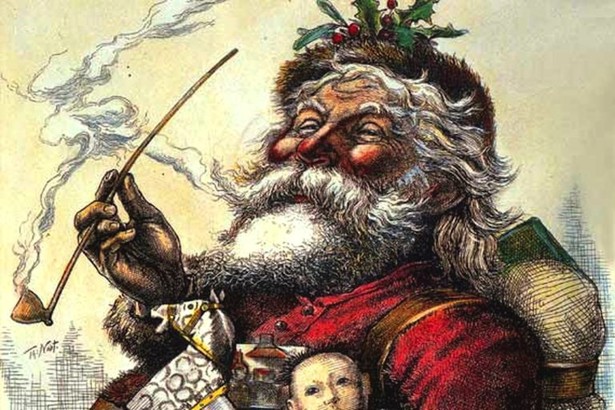

During the 1860's, the cartoonist Thomas Nast created a

new image of Santa Claus that replaced this ambiguous figure with a warm,

grandfatherly character who often appeared with his arms full of dolls, games,

and other secular toys. One of the earliest publications in which Nast’s Santa

figure appeared was the December 1868 issue of the magazine

Hearth and Home.

Christmas gift-giving, then, is the product of

overlapping interests between elites who wanted to move raucous celebrations out

of the streets and into homes, and families who simultaneously wanted to keep

their children safe at home and expose them, in limited amounts, to commercial

entertainment. Retailers certainly supported and benefited from this implicit

alliance, but not until the turn of the 20th century did they assume a proactive

role of marketing directly to children in the hopes that they might entice (or

annoy) their parents into spending more money on what was already a

well-established practice of Christmas

gift-giving.