The Virginia Republican will serve two years in prison for

corruption, capping his journey from the governor's mansion to the big

house.

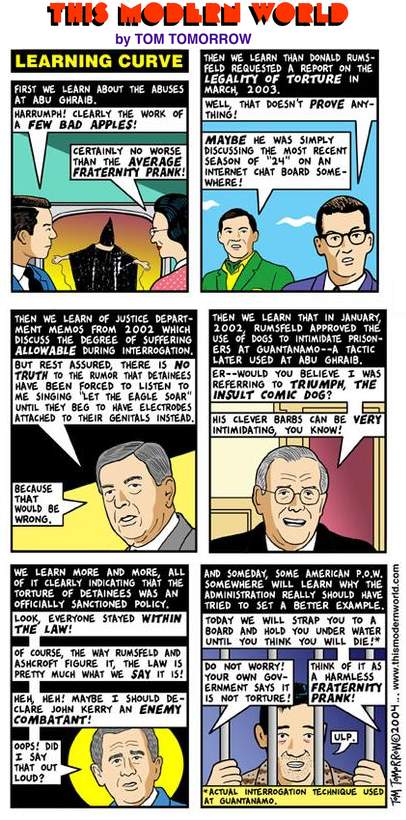

Bob McDonnell arrives at a courthouse in Richmond for

sentencing on Tuesday. (Jay Westcott/Reuters)

It's not often that two years in prison is a win. Then again, it's not often that a former Virginia governor is found guilty of corruption. Bob McDonnell is the first holder of that office to be convicted on such charges, and he'll pay for it with 24 months in prison and then another 24 months of supervised release.

That's far short of what prosecutors had hoped for. Citing the gravity of the crimes and charging McDonnell with remorselessness since his conviction, they sought 10 to 12 years, in line with their construal of federal recommendations. (Defense attorneys successfully persuaded Judge James Spencer that the upper limit should be more like eight years.) But it's also way more than what McDonnell's team had asked for: a breathtaking 6,000 hours of community service, with no jail time.

(It's hard to find an example of any sentence like that. Junk-bond king Michael Milken had to serve 5,400 hours, but only after a decade in lockup; the captain of the Exxon Valdez got 1,000.) McDonnell is expected to appeal the ruling.

One lament about this case—aired in this space by Amitai Etzioni, but also elsewhere—is that the real scandal is what's legal, and that we should be dismayed but not too rattled by McDonnell's case since there's far worse bribery that's sanctioned under law. The Republican was convicted of 11 counts of corruption for accepting $165,000 in gifts and loans from businessman Johnnie Williams, in exchange for official government favors.

But it's possible to be worried about the corrupting effects of legal money on politics and still view this as a triumph for justice. McDonnell was caught, tried, and convicted, and now he'll do his time. The justice system worked—and with a healthy assist from the Fourth Estate, and especially The Washington Post's Rosalind Helderman, which dug into McDonnell's transgressions. That's how American democracy is supposed to function.

The case was always surprising. First, McDonnell seemed squeaky-clean right up to the moment when it was clear he wasn't, and he was on list after list of Republican rising stars. He was destined for the national spotlight, perhaps as a vice-presidential candidate. Second, Virginia has for many years had relatively loose ethics rules, trusting (anachronistically, it's now clear) that its elected officials were gentlemen in the mold of Jefferson who would never sully themselves. As a result, the prosecution was a shock to the Old Dominion's old establishment.

Spencer in part agreed in his comments during sentencing. “No one wants to see a former governor of this great commonwealth in this kind of trouble,” he said, according to The Post. And he acknowledged the outpouring of support on McDonnell's behalf, even while imposing the sentence.

“The jury by its verdict found an intent to defraud. That is a serious offense that all the grace and mercy that I can muster, it can’t cover it all.” Spencer also said that the longer jail term sought by the prosecution "would be unfair, it would be ridiculous, under these facts.”

The two-year term is on the short end of the sentences given to some politicians in recent corruption cases, though apples-to-apples comparisons are tricky. The flamboyantly unapologetic Louisiana Democrat Edwin Edwards served a decade in jail. Former Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich, a Democrat, was convicted of more serious offenses including trying to sell a Senate seat and received 14 years in federal prison. His predecessor, Republican George Ryan, went to jail for more than six years on corruption charges. Former Connecticut Governor John Rowland, a Republican, was convicted of a single corruption count and served 10 months.

Much of McDonnell's defense hinged on blaming his wife Maureen, who was close with Williams. The strategy turned the trial into a painful can't-watch-can't-look-away spectacle, as the McDonnells laid bare their clearly troubled marriage in a court of law, under oath. Before sentencing, one of their daughters wrote to the judge, asking for leniency for her father and blaming her mother for the trouble. (Prosecutors, in turn, said this proved he was not contrite.) Spencer seemed to buy this, but only in part: "While Mrs. McDonnell may have allowed the serpent into the mansion, the governor knowingly let him into his personal and business affairs," he said.

Maureen McDonnell, however, will not be sentenced until February 20. The former governor asked on Tuesday the judge to be merciful with her—and perhaps this late gesture on her behalf, after the rather sordid trial, will be better than none at all.